Being a classical musician, I like to read biographies of the composers whose music I have performed. Learning a piece of music is comparable to a relationship with someone. You get to know the work, dig deep into all the different layers, melodies, musical sentences, harmonies, sounds that are supposed to be in the forefront, the ones that are supposed to be in the background. Songs do speak, and each musical sentence is saying something. It's important to listen closely to what you are playing so you can successfully carry that message over to the audience.

Bosephus Hambone is trying to decide which Mozart biography to read first.

As ballet dancers interpret sound through the motion of their body, I must produce that sound correctly so that it communicates what the composer intended to express.

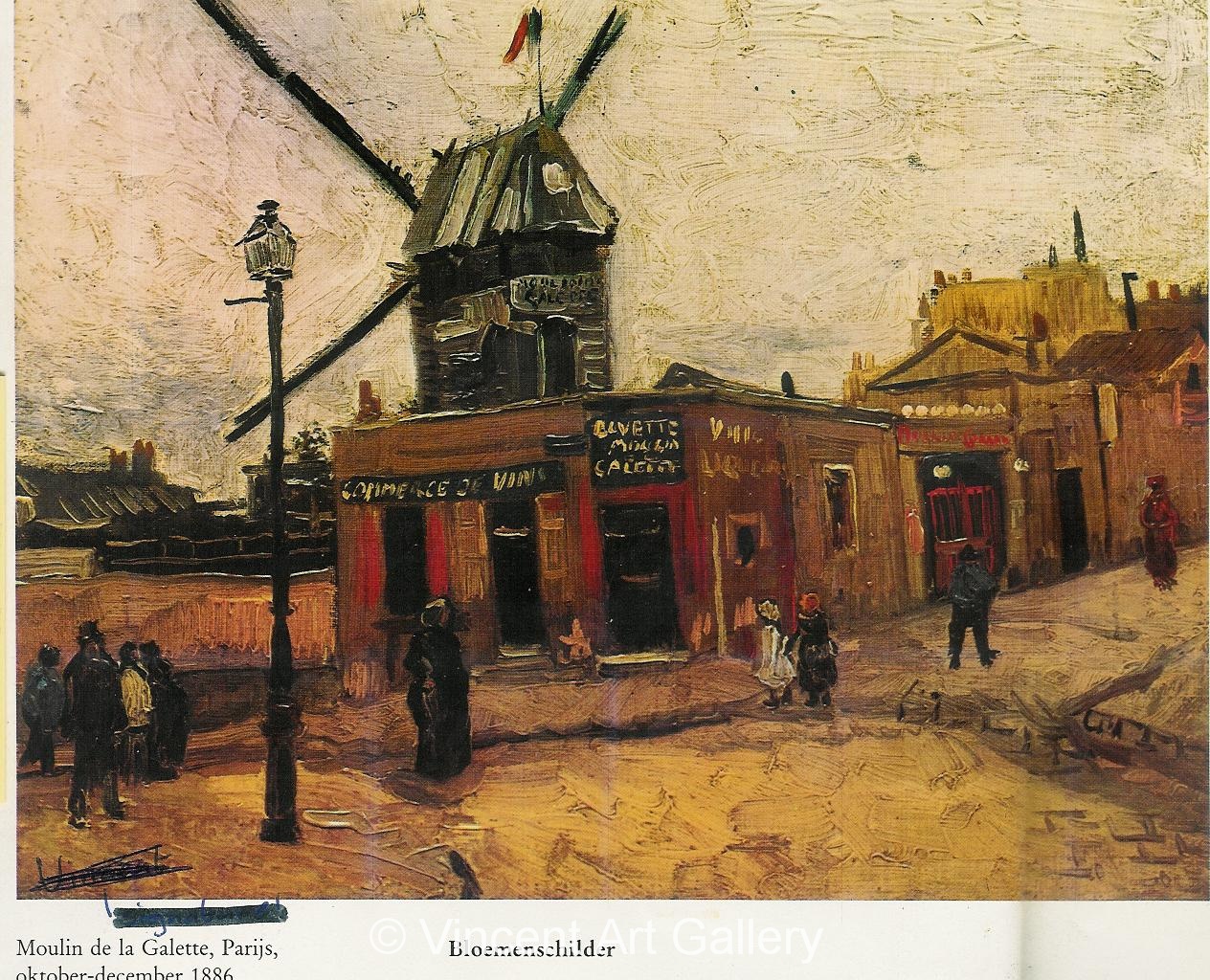

One of the things that helps me as an interpreter is to read up on the historical time periods of the composers. I read everything about those composers and also look at the art that influeneced the composers. I find that the art gives me a visual comparison to the aural experience I am trying to produce by playing a certain composition.

For example, what Rembrandt achieved with chiaroscuro in his paintings, Beethoven tried to create aurally. Chiaroscuro is the sharp contrast between light and dark. Here is a painting of Rembrandt to show what I mean:

If one listens to Beethoven's works, be it symphonies or a piano sonata, one can hear the great contrast between loud and soft, the whole orchestra playing, then suddenly one instrument playing. Fast vs. slow; calm vs. passion. His works are in constant flux between contrasting elements.

One thing I never did previously was read the letters of composers. I don't know, I felt it was an invasion of privacy. I have had a book of Mozart's letters for 28 years. It was a gift from the organist at my church in high school. Just a few months ago, I finally dusted it off and read it.

What a delightful collection! I then bought Beethoven's letters and enjoyed that too. Here is a brief description of both:

Mozart's letters are all the joy, cheer, brilliant wit and love of life that is expressed in his music put into words. The letters are primarily between the composer and his father. It is easy to see the optimist, naive, little boy with a wicked sense of humor who never quite grew up. All of his letters to his father are gushing about the latest friends he has made ("Count so and so loves my work he is going to commission me to write so many sonatas if I will travel to Italy with him etc...")

And his father's response: "Are you out of your feather-headed mind?! I told you to stay in Vienna where you can get a real job with a commission at the court."

I'm paraphrasing, but you get the idea.

Back and forth it goes. We learn a lot about the aristocracy and how they treated the little guy. Mozart was apparently a little guy. He was always strapped for funds and even though many wealthy patrons enjoyed his music, they weren't always intelligent enough to truly understand the genius behind it. They often treated him disrespectfully. Here's an excerpt from one of his letters:

So I presented myself. On my arrival I was made to wait half an hour in a great ice-cold unwarmed room, unprovided with any fireplace. At length the Duchesses de Chabot came in, greeted me with the greatest civility, begged me to make the best of the clavier since it was the only one in order, and asked me to try it. 'I am very willing to play,' I said, 'but momentarily it is impossible, for my hands are numb with the cold,' and I begged she would have me conducted to a room with a fire. 'Oh, oui Monsieur, vous avez raison,' was all the answer I received and thereupon she sat down and began to sketch in company with a party of gentlemen who sat in a circle round a big able. There I had the honor of waiting fully an hour...

At last, to be brief, I played on the wretched, miserable pianoforte...however, Madame and her gentlemen never ceased their sketching for a moment, so that I had to play to the chairs, tables and walls...

Then as likely as not, they wouldn't buy his works, or they would take them and not pay him for them. In short, Mozart was at the mercy of rich patrons who took advantage of him.

And yet he never lost his sense of cheer and joie de vivre which permeates throughout all his letters, counterpointed by his father's thunderous ones which provides us with a rollicking "storm vs. cheerful exuberance" kind of literary journey.

Also evident in his letters is his deep religious fervor. He changed his middle name to "Amadeus" which means "to love God". This is also expressed in all his music but especially in his masses. Mozart wrote over sixty religious works. He said:

I thank my God for graciously granting me the opportunity of learning that death is the key which unlocks the door to our true happiness.

And also his animosity towards those he deemed immoral. He wrote of Voltaire:

The ungodly arch-villain, Voltaire, has died like a dog. I have always had God before my eyes… Friends who have no religion cannot long be my friends.

The movie "Amadeus" portrayed Mozart as something of a womanizer but he wasn't. While he enjoyed flirtatious banter with various ladies, he explained to his father his intentions of marrying were for a number of reasons, including that, frankly, he didn't want to catch a disease. So Mozart was hopelessly romantic, which is evident in how he describes his beautiful, charming bride, Constanze, but also pragmatic. They had six children, only two of who survived.

Unfortunately, Mozart was not good with his finances, which were already distressed by fickle Royalty who were erratic with their payments. The last few letters in the book are addressed to a friend of Mozart who had lent him some money. These letters contain painful to read pleas for more money to help the young composer get out of his desperate straits.

The last letter included is by Constanze, who is asking the same man for money to help settle the now dead composer's affairs. A short epilogue is included to inform the reader that she was able to pay off all of her husband's debts.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 1756-1791

Bosephus has decided to start with the one by Marcia Davenport

Enthusiastically riding the wave of Mozart's letters, I immediately plunged into a collection of Beethoven's. This was after I read a good biography of his life by George Alexander Fischer. I have others to read but this one had very good foot notes and was well written and was free on kindle so a gem all around.

As bouncy and effervescent as Mozart's letters were, Beethoven's are deep, deep waters with powerful surges, creating tidal waves of emotion. They are not less or more beautiful but wonderfully different.

A few things surprised me. While Mozart could be impish to the point of immaturity in mocking people he deemed of lesser talent, Beethoven was surprisingly generous. In fact, he barely mentions anyone whose playing or composing he doesn't like but spends a great deal of time pouring out volumes of praise on those he did. His praise is not superficial or melodramatic but filled with love and honor. Among those composers he loved are J.S. Bach and his son, C.P.E. Bach. He kept in contact with C.P.E. Bach's son and worked hard to help him promote his father's work.

He sings the praises of Mozart, who, in one generation, had gone from relatively unknown to a national hero.

He also loved Handel, and also the poet Frederich Schiller-from whom he set the words to Schiller's poem, "An de Freude"-in English "Ode to Joy"- to the final movement of his Ninth Symphony (Joyful, Joyful, We Adore Thee).

He had a rather one-sided relationship with the great German writer Goethe. Beethoven loved Goethe and Goethe disliked Beethoven. This was because of an incident that Beethoven brought upon himself.

Beethoven and Goethe were walking down a promenade where the Empress was walking with her retinue. Goethe immediately stepped aside, took off his hat and bowed low until they had all passed. Beethoven, on the other, kept walking and talking, forcing the retinue to move out of his way as he passed. This shocked Goethe and he never had anything more to do with the composer.

This did not prevent Beethoven from admiring Goethe and he continued to write many works based on the writings of the great "German Renaissance man."

Another difference between Mozart and Beethoven as might already be imagined is that Beethoven did not do Royalty's bidding, they did his. He stormed out of a Prince's house after a perceived insult exclaiming, "There are and will be thousands of princes, but there is only ONE Beethoven!"

One thing in Beethoven's favor is that Royalty no longer held a monopoly on the patronage of musical composition . Primary funding came from publishers who bought the music and distributed it. Many of the letters in my collection are highly entertaining epistles to publishers from Beethoven who lets them know in no unclear terms exactly where they can go if they do not copy his music to his exact specifications or give him a cent less than the amount he demands for them.

Beethoven's great emotion comes surging out of his letters in the same way music propels off the pages of his compositions. He is almost bi-polar in his relationships. One letter is telling a friend how much he hates him and the very next is an abject apology for "losing control of himself".

One of the interesting things is Beethoven's devotion to obtaining custody of his brother's son from the mother. There are many court battles and as energetic and violent as Beethoven could be, the mother seems up to the task. It is a horrible case and the nephew at one point attempts suicide. Luckily he survives and eventually turns out well, a result he credits his uncle with.

Beethoven also loved many women, and to my surprise they loved him back and wished to marry him. In the end, however, he chose celibacy and never married. (I choose the word "celibacy" because that is the word used in the book. I know that flies in the face of our present culture that can't believe anyone not a priest would be so, but there it is.)

It's probably easy to remain celibate when you're chronically ill and Beethoven was chronically ill. As his hearing loss became worse, so did his spells of depression. It is a mystery how he came to lose it. Theories of congenital syphilis have been debunked because none of his siblings were affected with it and Beethoven was the oldest. An autopsy showed his inner ears to be inflamed. Probably and tragically it was something that could have been easily remedied today with antibiotics or tubes in the ears.

There were many other ailments, his liver, stomach, joints. He seemed as he aged to become enveloped in constant pain. He finally died at the age of fifty-seven. An autopsy was performed per his request and his liver was found to be shrunken. This could be due to many causes but the most likely is lead poisoning from drinking contaminated water and leaden cups. His body was found to have sixty times the amount above normal.

There isn't enough room to discuss Beethoven's music but a few things I found interesting was that he only wrote one opera, Fidelio, because he despised the vulgar and immoral humor that was prevalent in that genre (Mozart, who wrote twenty operas, apparently didn't have the same compunction) . He thought all music should be a religious experience. His opera was about the undying faithfulness of a wife to her husband. It was not popular during his lifetime, but later came to be understood for its greatness.

Then let us do what is right, strive toward the unattainable, develop as fully as we can the gifts God has given us and never stop learning. L. van Beethoven

Some have disputed Beethoven's religious views. He was born Roman Catholic but was not known for attending services. However, his views are best expressed in his Masses, of which he wrote several, and especially his Missa Solemnis. In the slow movement of his String Quartet No. 15 he wrote the title: "Holy Song of Thanksgiving to God from a Convalescent".

No friend have I. I must live by myself alone; but I know well that God is nearer to me than others in my art so I will walk fearlessly with Him. L. van Beethoven

What I found to be the most rewarding aspect of reading these great men's letters is that it seems as if they are talking directly to me. I am hearing their voice, crossing the boundaries of over a hundred years telling me their thoughts. That cannot but increase a sense of intimacy with them and I know that my performance of their works will not be the same.

Ludwig van Beethoven 1770-1827